BMR FORAGES WHAT WE SEE IN THE LAB

BMR forages include sorghums, millets, sudans, corn and hybrid variations such as sudex. BMR stands for brown midrib, the visible phenotype associated with the low-lignin genetic mutation. These forage varieties claim to improve animal performance when fed ad libitum. Improved digestibility increases the rumen passage rate. A rapid passage rate results in less time spent ruminating and more time spent consuming the forage. As feed intake increases, so does average daily gain.

In this article we will examine BMR forages compared with forages of an unknown BMR status. Customers submit sample to our lab and often label the forage species and sometimes indicate if the forage was a BMR variety. There are other studies available which compare BMR to non-BMR forages in controlled trials. Our data reflects what is actually available to producers throughout the region. Figure 1 shows the geographic locations of submitted samples. We have filtered our data to include sorghums, millets, sudans, and sudex hybrid crosses. We limited our analysis to sample with a dry matter between 85-100% to analyze hay samples. Other dry matter or moisture levels make it difficult to distinguish between silages and fresh forages.

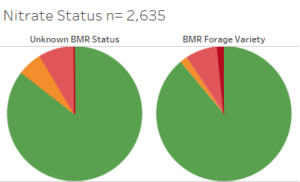

Nitrates

Although no claims have been made that Brown midrib forages have reduced nitrate toxicity risk, there are many antidotes claiming quality forages are less likely to harbor high nitrate concentrations. BMR forage species are known nitrate accumulating species. Therefore, we examined the potential for BMR forages to contain high nitrates compared to forages with unknown BMR status. Figure 2 shows a very similar nitrate toxicity risk between BMR variety forages and those with an unknown BMR status.

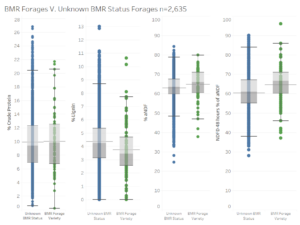

Nutritional Constituents in BMR v. Unknown BMR Status Forages

Brown midrib forages claim to have lower-levels of lignin, therefore increased digestibility. These claims do hold up when looking at the chemical composition of there forage varieties. First, in Figure 3 we can observe, that crude protein concentrations and the range of concentrations are not different in BMR v. unknown BMR status forages.

Next, we look at lignin concentrations. We can see that in an uncontrolled setting, or non-trial study, there is a large range of lignin concentrations in the BMR forage varieties. There is also range for aNDF and NDFD48. This range amongst these nutrients reinforces the need to test forages regardless of variety. There are production management and environmental factors that also affect the forage characteristics beyond the genetics. Returning to lignin, the interquartile range and average concentration is lower in BMR variety forages compared with unknown variety forages. Note there are BMR varieties in the unknown sample group being used to compare. So, a shift showing less lignin would likely be more dramatic comparing low-lignin varieties to non-BMR forage varieties.

Continuing, we observe a similar range of aNDF concentrations for Unknown v. brown midrib forage varieties. The average aNDF concentration is actually approximately 2 percent higher in the BMR forage varieties. However, this does not mean BMR forage does not live up to expectations. although fiber values are similar, we do see a slightly increased digestibility (~4% greater NDFD48) in BMR forages. Again, note there are BMR varieties in the unknown sample group being used to compare. So, a shift showing improved aNDF digestibility would likely be more dramatic comparing low-lignin varieties to non-BMR forage varieties.

So, are BMR Forages better than their non-BMR Counterparts?

In short, yes. BMR forages do hold up to their genetically superior claims. However, improved genetics can never be a band-aid or an excuse for improper or neglectful management. As we see in Figure 3, the characteristics of interest are variable and show a wide range regardless of genetic makeup. So, we need to manage our forages to the best of our operational ability. Furthermore, we need to analyze forages to formulate balanced diets and ensure we will meet animal nutrient requirements.