Nitrogen loss in saturated soils

____________________________________________________

Heavy rainfall in central Nebraska last week has caused crop producers to

question the availability of nitrogen (N) fertilizer applied this spring and

with good reason. Some fields may have experienced significant nitrogen

loss. There are several factors which will influence the amount of loss,

including rainfall amount and intensity, soil texture, soil temperature,

fertilizer source and application date. Loss pathways can include runoff,

denitrification and leaching.

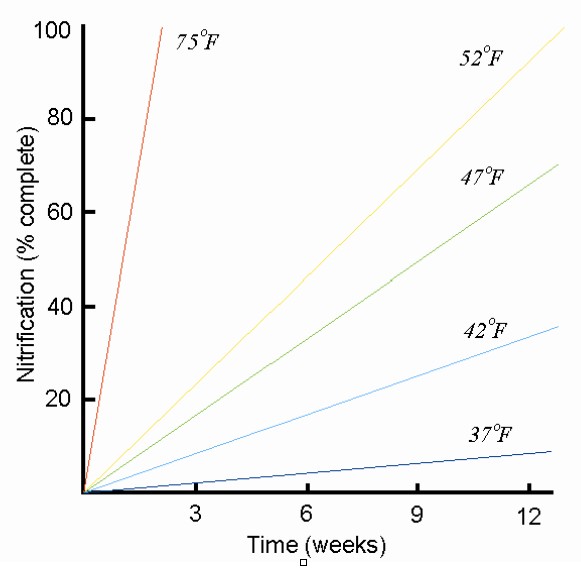

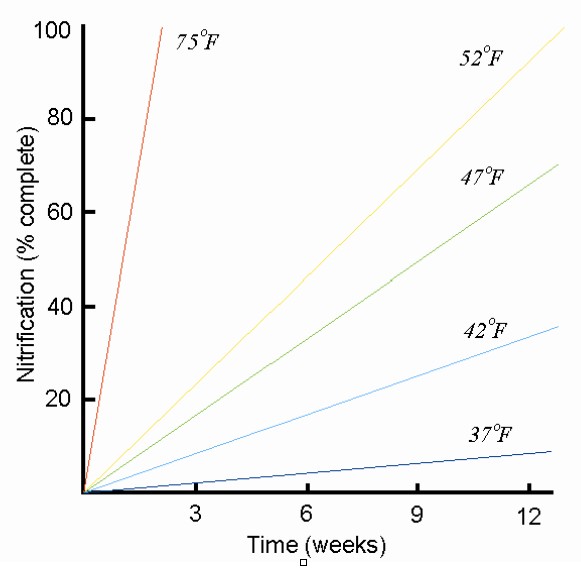

Figure 1. Estimated nitrification over time.

Runoff

If fertilizer had been recently applied to the soil surface, without

incorporation or a gentle rain of 0.5 inch or more to move nitrogen into the

soil profile, substantial nitrogen loss may occur in runoff. Rainfall was

very intense in some areas last week, with total precipitation exceeding 10

inches in some areas, resulting in severe erosion and loss of nutrients on

or near the soil surface.

Denitrification

The primary nitrogen loss mechanism from saturated, fine-textured soils may

be denitrification. This is the process of anaerobic bacteria present in

soil converting nitrate-N into gaseous forms (nitric oxide, nitrous oxide,

dinitrogen) which can be lost to the atmosphere. In fields where most

fertilizer nitrogen was applied preplant, likely four to eight weeks ago,

much of the N may have been converted to nitrate by the microbial process of

nitrification. This nitrate is then susceptible to loss via denitrification

or leaching.

Leaching

If nitrogen existed in soil in the nitrate or urea forms, significant

leaching loss may have occurred, more so on coarse-textured soils. Some of

this nitrogen may have leached deep enough into the root zone to be

unavailable to the crop, at least early in the season. Continued

precipitation or irrigation may leach this nitrogen out of the root zone

entirely.

For more information on soil processes influencing nitrogen management, view

the Nitrogen Chapter of the Cooperative Extension publication, Nutrient

Management for Agronomic Crops in Nebraska.

| Table 1. Potential field loss of nitrogen, depending on temperature and time since application |

Time |

Temperature |

N Loss |

(days) |

(degrees F) |

(percent) |

------------------------------------------------------------------- |

5 |

55–60 |

10 |

10 |

55–60 |

25 |

3 |

75–80 |

60 |

------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| Denitrification loss will be less with soils having less than 1% organic matter. |

Management options

Unfortunately, there are many variables interacting to influence the

potential for nitrogen loss from heavy rainfall, making it difficult to

estimate how much fertilizer N has been lost, and whether producers should

apply more fertilizer. Figure 1 and Table 1 can be used to help derive rough

estimates of potential loss. For anhydrous ammonia applied 6 weeks ago,

perhaps at least 50% of the nitrogen has been converted to nitrate. If soils

have remained saturated for a week, perhaps 10-20% of the nitrate nitrogen

has been lost to denitrification, with additional loss due to runoff or

leaching. Whether remaining nitrogen will be adequate to optimize yield

potential depends on the initial application rate, and growing conditions

during the rest of the season.

Soil sampling is one option to evaluate what is left, but results may be

difficult to interpret. If nitrogen fertilizer has been banded, many samples

will be required to integrate what the plant will have access to. Samples

should be collected to a depth of three feet in one foot increments.

Consider having samples analyzed for ammonium as well as nitrate, since

substantial nitrogen from many fertilizer sources may remain in the ammonium

form. Interpretation of soil test results for both ammonium and nitrate may

require help from a soil scientist. Even then accurate prediction of

fertilizer nitrogen availability will be difficult.

If producers can sidedress nitrogen or apply it through an irrigation

system, they may want to supplement loss they believe may have occurred. The

challenge will be to know what rate to apply. Over-fertilization will

increase the cost of production and potentially increase the loss of

nitrogen to the environment, while under-fertilization will reduce yield.

Carefully monitoring the crop for N status may be the best option, primarily

between now and silking, especially if producers have the option to

sidedress, fertigate or apply nitrogen with high clearance equipment. Most

corn hybrids will take up the majority of their nitrogen requirement in this

period. Visual observation for signs of nitrogen deficiency (lower leaves

yellowing, inverted "V" yellowing pattern of leaf tips) is one option,

although yield potential may be reduced by the time nitrogen deficiency is

visually evident. A chlorophyll meter may be useful in detecting nitrogen

stress before it can be seen. To calibrate chlorophyll meter readings, it is

best to have one or more strips in the field with nitrogen applied at a rate

high enough to be non-yield limiting to serve as a reference. For more

information on the use of a chlorophyll meter to manage nitrogen, see

NebGuide 1171, Using a Chlorophyll Meter to Improve N Management.

Richard B. Ferguson

Extension Soils Specialist